The Colorado River Basin is experiencing the worst drought in recorded history.

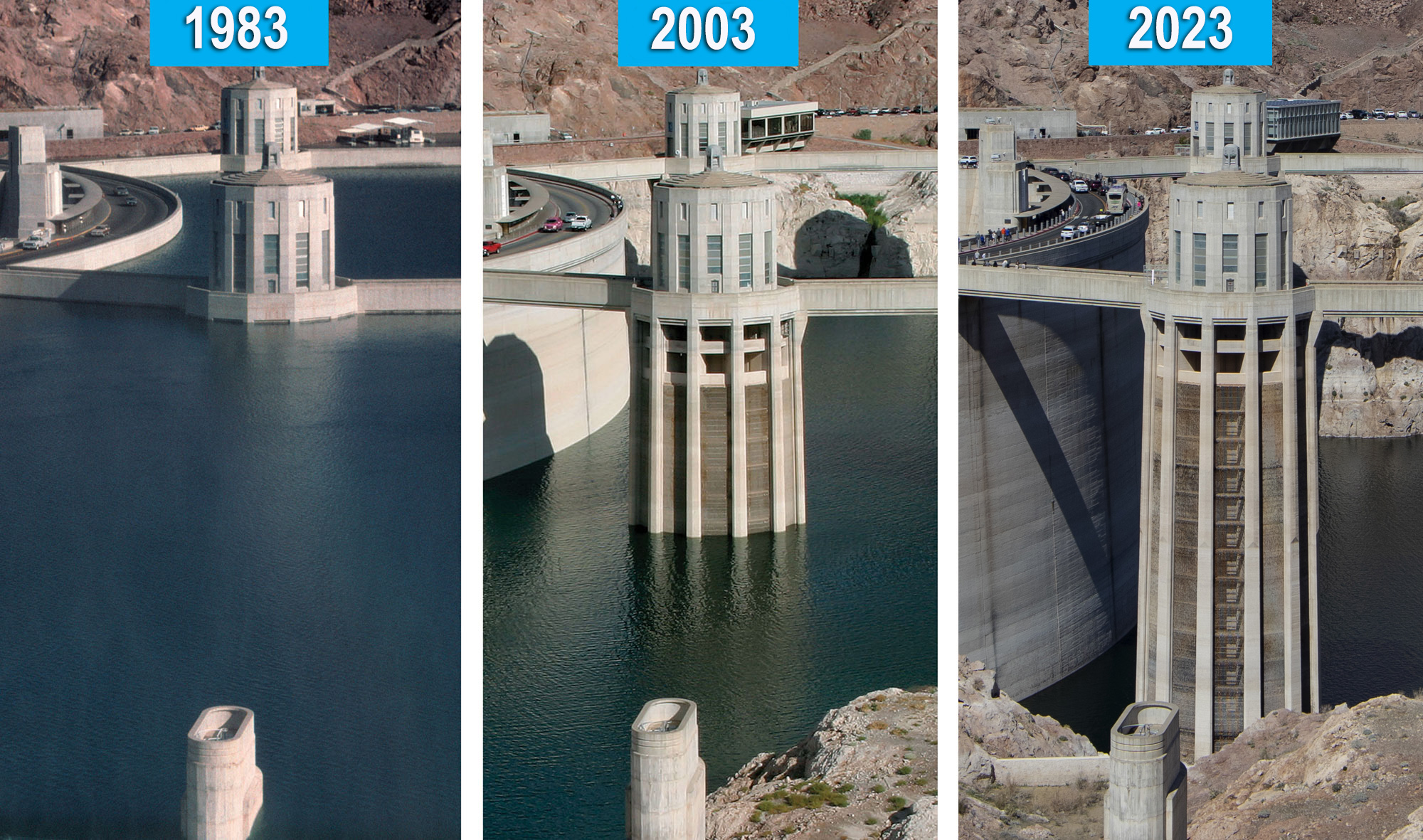

Since 2000, snowfall and runoff into the basin have been well below normal. These conditions have resulted in significant water level declines at major system reservoirs, including Lake Mead and Lake Powell.

The elevation of Lake Mead has dropped by approximately 160 feet since 2000. The Secretary of the Interior made the first-ever shortage declaration in 2021.

What you can do to conserve

- ✅ Follow mandatory seasonal water restrictions to reduce outdoor water consumption—which accounts for about 60 percent of Southern Nevada's overall water use.

- ✅ Replace nonfunctional grass with drip-irrigated trees and plants through the SNWA's Water Smart Landscapes rebate program (WSL).

- ✅ Prevent and report water waste (water flowing off a property into the gutter) to local water utilities.

Current condition: Tier one water shortage

A tier one shortage is currently in effect, reducing Nevada's consumptive Colorado River water use by 21,000 acre feet.

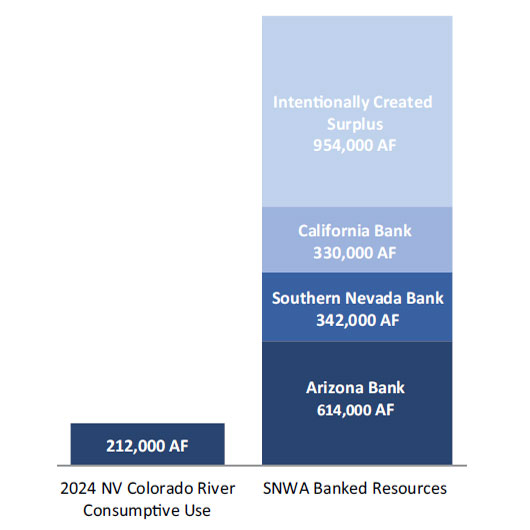

Nevada is not currently using its full Colorado River allocation, and near-term shortage declarations will not likely impact current customer use. By the end of 2024, Nevada's consumptive Colorado River Water use was 212,400 acre-feet. This amount is below any Colorado River water supply reduction under existing rules.

What agreements are in place?

Federal, state and municipal water providers in the Colorado River Basin have worked together for more than a decade to slow the decline of Lake Mead water levels. The 2007 Interim Guidelines for the Coordinated Operations of Lakes Mead and Powell and the 2019 Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) are two agreements that benefit Nevada and other Colorado River water users.

Among other things, these agreements:

- Keep more water in the river for the benefit of all water users and the environment.

- Help slow Lake Mead water level declines to preserve critical reservoir elevations.

- Allow for water banking in Lake Mead in the form of Intentionally Created Surplus.

- Draw participation from new stakeholders, including California and Mexico.

Interim Guidelines

The Bureau of Reclamation issued detailed guidelines in 2007 that mandate how Colorado River water stored in Lake Mead is managed during a declared shortage.

Under a shortage declaration, the amount of Colorado River water available to Nevada and Arizona is reduced. The Secretary of the Interior makes a shortage declaration for the following year when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's model projects Lake Mead to be at or below 1,075 feet on January 1 of the following year. The model is run annually in August.

Shortage amounts vary by state and are based on Lake Mead water levels. Nevada's shortage volume ranges from 13,000 to 20,000 AFY.

Drought Contingency Plan

Congress authorized implementation of the Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) in 2019. Under this agreement, Lower Basin States will begin making DCP contributions when the elevation of Lake Mead is projected to be at or below 1,090 feet.

Contribution amounts vary by state and are based on Lake Mead water levels. Nevada's DCP contribution ranges from 8,000 to 10,000 AFY. This volume of water is in addition to any mandatory reductions associated with a federally declared shortage. Nevada will receive credit for its DCP contributions. These credits can be recovered when Lake Mead is above 1,110 feet. Below this elevation, Nevada can access or borrow its credits, subject to certain restrictions.

Reservoir Protection Conservation

The Secretary of the Interior signed the 2024 Near-term Operations Record of Decision (ROD) in May 2024. The ROD implements the Lower Basin's commitment to conserve 3.0 million acre-feet of water as Reservoir Protection Conservation (RPC) through 2026, helping to address critical elevations at Lake Mead and Powell.

The ROD supplements the 2007 Interim Guidelines, addressing the potential for continued low runoff conditions in the Basin. The SNWA contributed 233,000 acre-feet of water toward the RPC commitment through 2024. Collectively, the parties have saved approximately 2.03 million acre-feet. Southern Nevada remains committed to ongoing participation through 2026 to preserve storage and bolster Lake Mead water levels.

Nevada's combined reduction under the Interim Guidelines and DCP ranges from 8,000 to 30,000 AFY, depending on Lake Mead’s water level. These agreements expire at the end of 2026 and stakeholders are currently negotiating rules for post-2026 Colorado River operations.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's 2025 August 24-month study forecasted a Lake Mead elevation between 1,050 feet and 1,075 feet for Jan. 1, 2026. A tier one shortage will remain in effect through 2026 for Lower Basin operations. Under this shortage designation, Nevada's available Colorado River supply is reduced by 21,000 AFY.

| Lake Mead water level | Shortage amount | DCP contribution | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Above 1,090 feet | 0 acre-feet per year | 0 acre-feet per year | 0 acre-feet per year |

| At or below 1,090 feet | 0 acre-feet per year | 8,000 acre-feet per year | 8,000 acre-feet per year |

| At or below 1,075 feet | 13,000 acre-feet per year | 8,000 acre-feet per year | 21,000 acre-feet per year |

| Below 1,050 feet | 17,000 acre-feet per year | 8,000 acre-feet per year | 25,000 acre-feet per year |

| At or below 1,045 feet | 17,000 acre-feet per year | 10,000 acre-feet per year | 27,000 acre-feet per year |

| Below 1,025 feet | 20,000 acre-feet per year | 10,000 acre-feet per year | 30,000 acre-feet per year |

Hoover Dam

Hoover Dam regulates Colorado River flows, provides water storage and produces hydroelectric power to Nevada, California and Arizona. The dam created Lake Mead, which stores Colorado River water for the lower basin states of Nevada, California, Arizona and the country of Mexico. Each of the Lower Basin states receives an annual allocation of Colorado River water as detailed in the Boulder Canyon Project Act.

Lake Mead can hold almost 9 trillion gallons of water. However, due to ongoing drought conditions and a hotter, drier climate, the lake's elevation has dropped by approximately 160 feet since 2000, and water levels are expected to decline even further. If Lake Mead falls below 895 feet in elevation, or dead pool, water cannot flow through Hoover Dam to California, Arizona and Mexico.

▶️ Watch to learn more: What happens to Southern Nevada if power pool is reached at Hoover Dam?

Climate change

Drought has become synonymous with the Colorado River over the last 24 years. This term can be misleading, implying a transient condition that will end. Evidence supports the fact that climate change is happening now and that it will have a lasting effect on the availability of Colorado River water supplies.

Today, the best scientific projections available suggest that current Colorado River conditions will not only continue but worsen. Leading climate scientists warn of a permanent shift to a drier future, something known as “aridification.” In simple terms, aridification refers to drying conditions that result from warming, and it represents long-term change rather than seasonal variation or periodic droughts.

While climate change models project that warming trends will continue, the magnitude of change at a given location will depend in part on global mitigation efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Nevada's Clark County is projected to warm between 5 - 10 degrees by the end of the century. In Southern Nevada, the impacts of climate change are expected to be similar to that of drought. This includes extended durations of low Lake Mead elevations, water quality changes, possible reductions of Colorado River resources, and potential increases in water use to compensate for warmer and drier conditions.

The 2020 State of the Science Report confirms that temperature trends in the Colorado River Basin are increasing and precipitation, snowpack water volume and annual streamflow trends are decreasing.

Adaptive management

The Water Authority is responsible for anticipating future water demands and taking the steps necessary to meet them. Over the years, the agency has taken a number of adaptive management steps to reduce the impacts of drought and climate change on water supplies and facilities.

- Through one of the nation’s most progressive and comprehensive water conservation programs, Southern Nevada has reduced its per capita water use by 55 percent between 2002 and 2024, even as the population increased by approximately 829,000 residents during that time.

- The Water Authority has constructed a third drinking water intake and a Low Lake Level Pumping Station at Lake Mead to ensure continued delivery of Colorado River water to Southern Nevada under low reservoir conditions.

- Through compliance and sustainability efforts, the Water Authority seeks a balance between water resource use and environmental stewardship, including species habitat conservation and protection.

- Through water banking efforts in Nevada, Arizona, California and in Lake Mead, the Authority has stored more than 2.2 million acre-feet of water. This is 11 times Nevada's 2024 consumptive Colorado River water use. Like a savings account, water banking provides the Water Authority with the ability to store water for when it is needed.

Continued water conservation and adaptive management are ongoing priorities as our community responds to drought and climate change.